Generative anthropology either gets lavished praise or a bad rap on the internet. Especially within social media—which is rather strange given its nearly invisible internet presence. In academic institutions and with those who have ties or jobs within them, GA has a pretty strong vitality to it. Yet, for some reason, it has a real volatile—conversation killing—quality on mass media platforms. Is this a good thing? If not, then why would that be?

I’ve written a lot about generative anthropology in these monthly posts. A lot of my views and dispositions have changed; sometimes from direct comments on my direction, sometimes it has been wisdom from an argument I as well had. Initially coming across GA from a little research I had done, I have known of it since I was 15. Many of us know the gulf that exists between ourselves in our budding teens and the exit into adulthood, let alone the bigger gap beyond that into our 20s—where I now reside. So, it should be no wonder my own opinion has waxed and waned over the years.

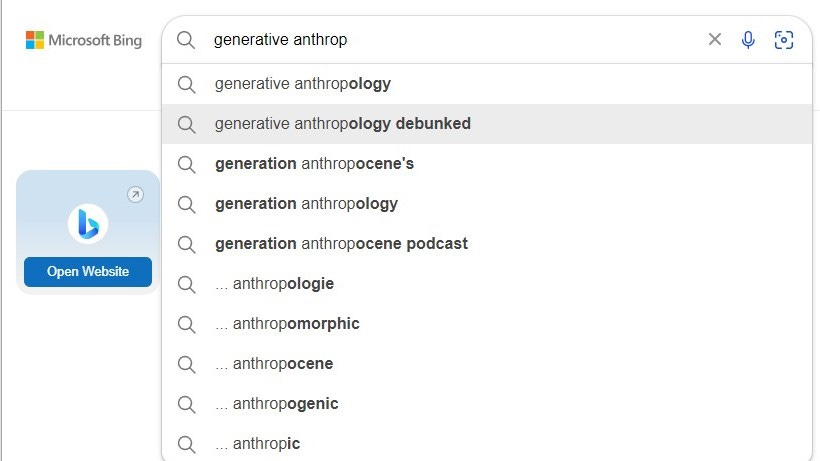

At least on my Bing search engine, whenever I look up, in a naked search, “generative anthropology" one of the first suggested searches is “generative anthropology debunked”,

From there, if you go along with the search, you are led to a few pages. Most of the Wikipedia entries have, now, after some years, been updated—thankfully. The other few are obviously from the Absolutist Neo-Reactionary subreddit, where most of the new GAblog is re-posted, and reasonably avid discussion takes place (you can find the old blog here). Among those search results is also Adam’s review of Zlocka-Dabrowska’s new book, and a few other notable inclusions. While these are certainly interesting, our focus for this search “generative anthropology debunked” lies primarily in a video by TrueDiltom—of the same name—and a publication to the (now dead?) journal Firstness—”Generative Anthropology is Bullshit”.

Most of my counterarguments are already stated in the reddit thread, linking to the video claiming to debunk GA (although the video itself never shows up in the search). My primary argument I had made when the article for Firstness was released was simply, “Where are the citations to Gans’ books?” This isn’t to say that it is impossible to gleam an adequate theory of generative anthropology from its ancillary sources, but at the very least the Origin of Language should be included. If you would want a thorough and rigorous case—and an example I would back as good faith—on the problems of generative anthropology, see to this old Brussels journal entry. The comments are fairly self aware and really demonstrate an interesting discussion on how people come to hear of the thesis of generative anthropology. To juxtapose, here’s a complimentary book review that is a decent model for critique, also—also done by what seems to be another UCLA affiliate. He interweaves his own theme of the intellectual divide between Gans and Girard, while keeping a general poise about it. The division between Gans and Girard isn’t really mentioned at all, except in the conclusion, in Generative Anthropology is Bullshit. Given that Gans was a student to Girard and mentions him as one of the greatest influences in his work, it should be a primary focus—rather than the Derridean dialogue that is, rather, found there.

There is not too much to complain about, here, except for the lack of institutional criticism. Most of the primary search results actually lead you to ‘introductions to GA’ and wikis explaining it, firstly. So, perhaps that is disappointing not to find our scathing reviewer out in the wild. Personally, I have refined my own analysis of why GA hasn’t institutionalized academically and will be presenting one particular solution to that. It was inspired by Gans’ second book End of Culture; notably where he entertains a “strong” and “weak” hypothesis on the origin of language. For my research, I have divided that kind of format of strong and weak variations into a more literal historical argument related to the originary hypothesis. Then, introducing the “weaker” theory of language that results from the consequences of that initial hypothesis. If one were to read, and pay specific attention, to the articles and terms Gans uses in both the beginning of Scenic Imagination and A New Way of Thinking, they would find Gans separates hypothesis, theory, and other scientific terminology already. Gans can be tricky and I try to discuss a part of what he actually is meaning by this hypothesis of the origin of language, in my recent essay Dzogchen and the Scenic Imagination.

Given that my own article appears when you search for Gans and GA, I should do well to update that, too. Which I plan to have done once I’ve finished more of the supplementary work. In essence, my plan is to develop a small curriculum around various study guides for Gans’ books. This way we don’t run into these problems of people writing up lengthy rebuttals to arguments that could have just been taught, without needing to resort to primary sources. While, perhaps to me, it seems rather stupid to not just buy the books that explicitly detail the theory and history of GA (I don’t have such strong opinions on sociology to write an essay on its unecessary-ness); it seems to be an inevitable consequence of GA’s online presence.

There is more to discuss about the discussion’s GA has had over mass media outlets, like Twitter, but they really are rather boring. If we take the measurement of traditionally academic and institutionalized rigor to be our leading sentiment for publications and essays, and those such article and journals don’t meet the marker for that high bar, then what do we expect of media outlets?

Epistemic Disputes and Leadership

I figured I would link to some sources and models for people who still wish to fight against GA. Currently it seems many of them are just fighting phantasms, so I figured I would link up some more tangible enemies if they wanted to really fight them. I have my suspicion that most of them have moved on—and realistically just wanted to make a persuasive point that for their individual groups they don’t need to address GA, as I will demonstrate shortly. The idea being, that they might not even care for the more rigorous arguments because the answers wouldn’t pertain to them (why care about the various historical placement of tool use in regards to the originary hypothesis, e.g.?). What does all that really have to do with political theorists and commentators, until someone starts making arguments citing those more detailed remarks in relationship to political theory? The entire idea of that Generative Anthropology is Bullshit article is situated there. It accepts and relinquishes Adam Katz’ political theory and contributions but decides that whatever else involving the theory isn’t really worth the trouble:

The implications of this regarding Generative Anthropology are pretty simple. It isn't a good theory and those interested in political theory should look elsewhere. However, the epistemic issues here are illuminating as they speak to a broader problem with spurious pet theories that gain an undue degree of prominence in online substructures where they are not subject to an adequate degree of scrutiny as the skills and knowledge needed to adequately scrutinize them are not widespread. For example, the argument made here against Gans is applicably almost in its entirety to his far more popular mentor, Rene Girard. The sentimental attachment to an equally speculative hypotheses of a perennial tradition amongst so called Traditionalists is another notable case of sloppy thinking. Far worse is the endorsement of outright woo perpetrated charlatans like Sheldrake and Steiner.

To tackle Hunter’s epistemic remarks; the degree that I have seen people adopt GA rhetoric online, this is fairly true, in a sense. As I state above, the Twitter and media comments are fairly unmemorable. I am making the case, right now, that many people are sloppy with how they approach generative anthropology. So to demonstrate what I am meaning, rather than rehash Hunter’s argument in detail, we will go into a better example of this type of argument over epistemic quality. In this case I will refer to William Irwin Thompson. To agree with Hunter’s above criticism, I have even historically aligned with same critique of Steiner that William Irwin Thompson’s does in his book Coming into Being: Artifacts and Texts in the Evolution of Consciousness:

In his book Cosmic Memory, Rudolf Steiner claims to be able to take us to the edges of history in an archaeological excavation that he calls “reading” the akashic record—the etheric image in the structure of space-time that holds the record of the past. But one needs to remember that the template for registering this crystalline structure is Steiner’s own imagination. The akashic record is not like a CD-ROM; even for an amazing clairvoyant like Steiner, there is a hermeneutics to the imagination, and what Steiner “sees” is a negotiable instrument that brings forth a relationship between himself and the akashic record of the collective unconscious. Steiner’s imagination is a product of his time; it is influenced by Ernst Haeckel’s nineteenth-century Darwinian narratives and by the physics of the turn of the century. (77)

But notice how Thompson takes Steiner at face value and subjects him to his own rules. Here he makes a more notable case towards metaphor and literalism, which proposes an actual amount of epistemic persuasion to a follower of Rudolf Steiner:

Literalism is very often the affliction that followers inflict on their more imaginative leaders. The followers degrade the movement, and everything the leader has tried to do becomes a rigid and ridiculous caricature of itself. Steiner fell into the sacrificial role of leader and played out the tragedy of followership for all of us to see. One disgruntled follower burned down his Goetheanum, and another probably poisoned him. A remnant of his followers have embalmed his remains in a humorless cult of nineteenth-century folk romanticism, in terrified flight from the demon Ahriman and his servants in the modern electronic world. There is a shadow side to all leaders that gets unconsciously picked up and acted out by their followers.

When a great initiate such as Steiner drops into incarnation in too heavy a fashion, he creates a big splash, and that cultural splash creates the opposite reactions of followership with the Anthroposophists and decayed German romanticism in Hitler’s fascination with the occult. It is better to slip into the waters of human incarnation silently, like a frogman, and swim out to attach magnetic bombs to the battleships of industrial materialism. Steiner certainly was no Fascist; in fact, the Fascists were out to get him, so he had to make his base in Switzerland. Steiner lived with a Jewish family, was a teacher of a hydrocephalic Jewish child, and actually took this eight-year old who was considered a vegetable and worked with him so that the child grew up to become a doctor —which is certainly an impressive achievement. But the cultural reaction of the intense leader-led romantic movements of spiritual renewal created the shock waves that gave us Wagner and Hitler. (79)

The testament and idea behind Hunter’s work (which I consider the most recent, relative apotheosis of GA criticism) is outdone by someone far more empathetic like Thompson. If you actually follow Rudolf Steiner’s own writings, you see easily that Thompson has read Steiner’s books (as the quotation suggests with Cosmic Memory) and then presents numerous historical moments that back his theory of the various lunatics that surround Steiner’s legacy. My problem with Hunter is just that he doesn’t discuss the history of Gans much like Thompson does Steiner. Girard is included as an appendix and add-on, in comparison. If you ask the harm that GA does, then you’re led to a dead end; its lack of institutional place seems to be its own punishment (in that regard), does it not? For me, I care about the academics who have toiled away for decades to ensure GA has a heartbeat. As I am pointing out, that is really more where “true” followers of GA reside, where harm could be done. Hunter sketches an okay argument for a very specific subsect of online people who do online philosophy and care about online statements about politics—to which GA might bog their waters.

While one of my own major influences was, indeed, John David Ebert (to whom I found Thompson and his books in his Texts: Collected Book Reviews), clearly Ebert’s own apathy to his lack of institutional placement in academia is the same problem as we have outlined above (maybe even more tragic). He has clearly read Thompson and reviewed his work—applying a critical acumen to each text—but maybe he just disagrees with the sentiment behind the above quotations. In my eyes and in Thompson’s eyes, I imagine Thompson’s intention was to outline a pretty memorable and honorable history of what it means to be too individualistic. Furthermore, what type of followers and influence that leaves behind, or is at a danger of leaving behind. GA can come across as falling pray to “lunatics” picking it up, given that there is an immense duty laid upon the reader. Even then, Gans’ incessant demands for parsimony should be more than enough to institute some good faith search for his various claims, as well as serve as valid enough criticism.

There are just more subtle ways we can go around this problem of communication, by clearing up the brush of Gans’ own rhetoric (in those Brussels comments, they lament the same, but recognize Gans’ many influences, unlike every GA debunking I’ve seen so far). However, we don’t need to toss the entirety of GA out the window simply because it was written by and upheld by academics and professors (who desire an almost insatiable amount of de rigour); that is to say, a group of individuals who are conditioned to citations and multiple influences which lead to a vague “gatekeeping” quality. Viewing that in another light, from the perspective of an academic, they don’t mind and really do enjoy unique perspectives, so the criticisms of GA lie in this, almost, psychological territory. If I had to issue a takeaway, here, let us not focus so hard on the faults of individual writers, because they cannot meet the standards and anticipate the needs of every reader they encounter. To quote Adam,

Don’t forget, in appropriating the formula “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs,” that the able have needs of their own, in many ways more urgent and consuming of resources than those of the merely needy

To end this off, lets answer our initial questions. Is it a good thing that GA only has a spurious online presence in mass media? Perhaps in some ways, yes. Do we expect those who write of sociology on social media to be familiar with Durkheim’s specific thesis’? But in other ways, no. Maybe GA is, indeed, due for some study guides and for some well needed spring cleaning. I’m doing my best to try and help that, but it never quite is so easy. Nor do I really care about what exactly online strangers immediately disagree with considering the premises of GA. Having read Gans’ books I have made up my own mind on the subject, I expect others that would do the same as I have done—I am no academic. What we need most right now is just fruitful collaboration and to stop declaring things “dead”. No one is really to blame, ultimately, for how could we blame any one person? The best we can do is make amends and look forward to better futures and less misunderstandings among us all. It just may be a bit of a prickly path forward.

"Debunking" itself is kind of silly - the idea that you'd just want to terminate any line of inquiry past some point where the inquirer was "incorrect," according to whatever subjective conditions of "incorrectness" that you're working with, and refuse to acknowledge any statements made past that point. There are spaces where an argument could be made that it's necessary - mathematics, for example - but philosophy? Anyways, I do sympathize with criticisms of GA's lack of respectable epistemic rigor, but the types of institutional structures necessary for such rigor can't be built overnight. There's like, maybe 10 people doing work with Adam's originary grammar right now. That number should begin to change once courses and learning materials get finished and the necessary incentive structures set up for people to learn and do research.